Billy’s Bill or Just Bull, Part II: Emails Tell the Story.

- Apr 23, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Sep 24, 2025

By James Townsend

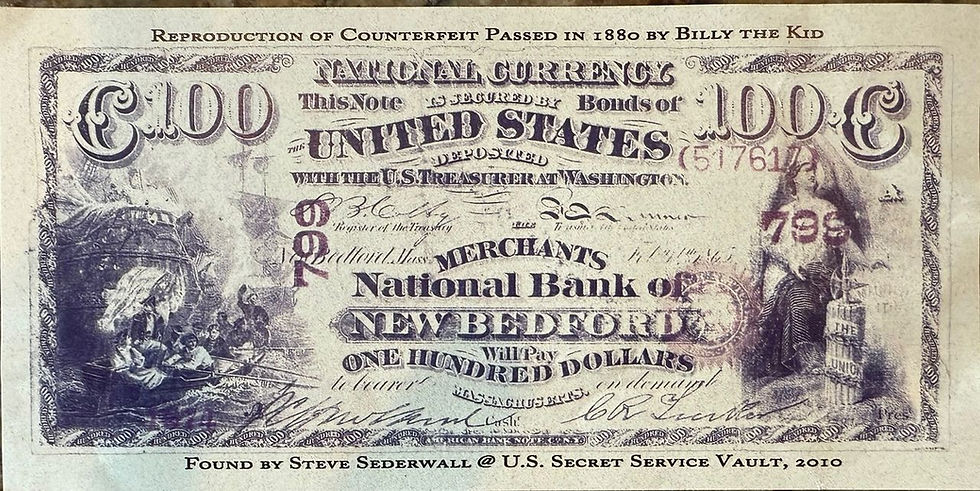

A replica of the counterfeit bill Steve Sederwall received from the Secret Service-later handed out as a promotional gimmick with false claims that it was passed by Billy the Kid in 1880. It wasn't. The serial number doesn't match, there were no historical markings, and the so-called "Secret Service vault" never existed. Just another prop in the ongoing Sederwall circus.

Getting history wrong is inevitable. Sometimes we trust the wrong source. Sometimes we follow a hunch too far. But when new facts come to light, honest historians correct course.

That’s not what happened here.

In the first part of this series, I detailed a misleading claim made by Steve Sederwall. He presented a counterfeit $100 bill—serial number 517617—as the very one passed by Billy Wilson to James Dolan in Lincoln, New Mexico, in 1880.

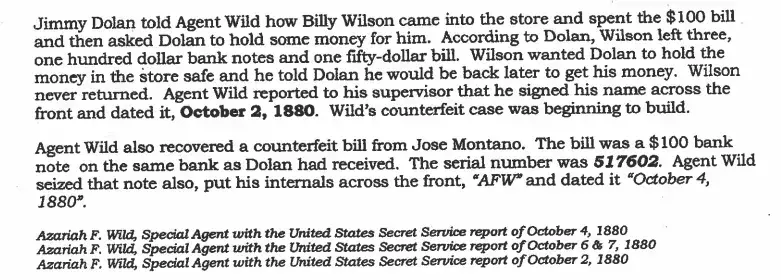

That claim was already on shaky ground. Secret Service records from the time, specifically the reports of Agent Azariah Wild, identified the bill passed by Wilson as serial number 517607. A different number. No sign of alteration. And most notably—none of the handwriting Wild described. According to his 1880 report, Dolan marked the bill with a “D,” and Wild himself signed his name across the face with the date written below.

In another email to the Secret Service, Sederwall recounted details from Agent Wild's 1880 report: Jimmy Dolan claimed Billy Wilson left three $100 bills and a $50 in the store safe-never to return. Wild seized the bill, signed it across the front, and dated it October 2, 1880. A second bill, recovered from Jose Montano, bore serial number 517602 and was similarly marked "AFW" with the date October 4. Sederwall's own words confirm he knew the authentic bills were clearly labeled-yet the one he promoted showed no such markings.

The bill Sederwall showcased had none of it. Not a single mark. Just a counterfeit bill from the right bank—wrong serial number, no historical identifiers, and no connection to Dolan, Wilson, or Wild.

At first, you could chalk it up to an honest mistake. Maybe Sederwall didn’t know the full details of the original bill. Maybe he thought it was close enough.

But that’s not what the evidence shows. Thanks to a successful request to the Secret Service archives, we now have copies of every email exchanged between Sederwall and the agency. Along with them, we received the original photos of the counterfeit bills sent to him.

What the documents reveal is something far more troubling than a historian with incomplete information.

On January 5, 2010, Steve Sederwall sent an email to the Secret Service:

January 5, 2010 — Steve Sederwall emails the Secret Service, not in search of truth, but in search of a headline. "Any bougas [sic] note will help," he writes, pitching a potential PR stunt: if he can find the plates, "'ll cut you guys into it."

“Here is what I am looking for; any bank note from the Merchants National Bank of Bedford, Massachusetts. I am most interested in the serial numbers below but any bougas [sic] note from that bank would help… I am on the trial [sic] of the plates that were never found. If I can run them down I will cut you guys into it and this could be a good PR thing.”

This wasn’t a historian requesting verification. This was someone fishing for props to complete a prewritten story.

He continues:

“Wild took the bill and put his internals [sic] across the front and dated it.”

That line is key. It shows he was already aware—before receiving any materials—of what the original bill was supposed to look like. He knew it had a signature. He knew it had a date. He even knew what serial number it was supposed to be.

Yet he took a completely different bill—one he specifically requested as any counterfeit from that bank—and began marketing it as the legendary Dolan bill.

He made Facebook posts. He gave interviews. He published articles, including one titled Billy Bonney’s Bad Bucks, claiming this note had been passed by Billy Wilson himself. He suggested a serial number had been altered—a zero turned into a one—to explain away the discrepancy. Never mind that no tampering is visible. No altered ink. No reworked numbers. Just a clean “1” where there was supposed to be a “0.”

Even more damning is what the Secret Service told him in return. Their reply reads:

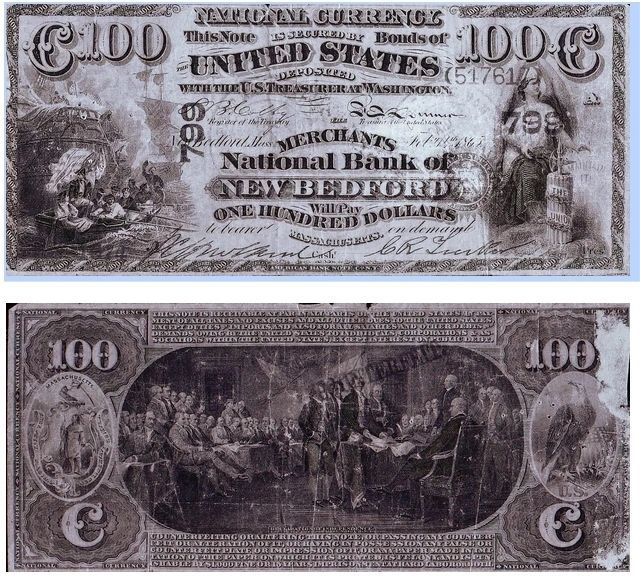

“Per your request, we conducted a search and located some relevant information. Included are two black and white photographs of a counterfeit $100 Merchants National Bank of Bedford, Massachusetts bank note, series 1865.”

There it is. They never claimed it was the Dolan bill. They never confirmed any connection to Billy Wilson, Lincoln, or Wild’s investigation. They simply sent him what he asked for—any bogus note that fit the timeframe.

Sederwall’s version of events? That this was the lost note, a forensic discovery, an Old West cold case solved?

That was fiction.

And he knew it.

This wasn’t just bad history. It was staged history. Manufactured. Presented to the public with confidence, knowing full well the source material didn’t support the claim.

Why? Maybe it was the thrill of the find. Maybe it was the attention. Maybe it was something as simple as brand-building—Cold West Detective Agency style.

But at the center of it is this: Sederwall knew better.

He had the serial number. He knew what was written on the bill. He asked for anything that might look close enough. Then he filled in the rest with imagination.

It’s easy to look at someone like Sederwall and see a colorful storyteller. But stories sold as fact—when they’re not—undermine all of us who try to get the record straight.

Let’s be clear: counterfeit bill 517607 has never been found. That’s not speculation. That’s fact.

Yet Sederwall’s article is still out there. His Facebook posts still circulate. And people who care about Billy the Kid’s history are left sorting truth from the Sederwall circus.

It didn’t have to be this way. An honest admission that the bill was from the same bank, possibly the same batch, would’ve been a fascinating footnote. But Sederwall didn’t want a footnote. He wanted a headline.

And the truth got buried under it.

The U.S. Secret Service provided Steve Sederwall with two black-and-white images of a counterfeit $100 bill from the Merchant National Bank of Bedford, Series 1865-along with clear reproduction guidelines and instructions to credit the agency. Sederwall

failed to do so. Despite being told the images were provided simply as relevant materials-not as proof of connection to Billy the Kid—the photos were later used in public claims that ignored both attribution and historical accuracy.

Comments